What are the "experts" in Mixture-of-Experts LLMs?

And how can 8 or 16 of them cover all possible domain of expertise?

This is episode 5 of a series of shorter blog posts answering questions I received during the course of my work and reflect common misconceptions and doubts about various generative AI technologies. You can find the whole series here: Practical Questions.

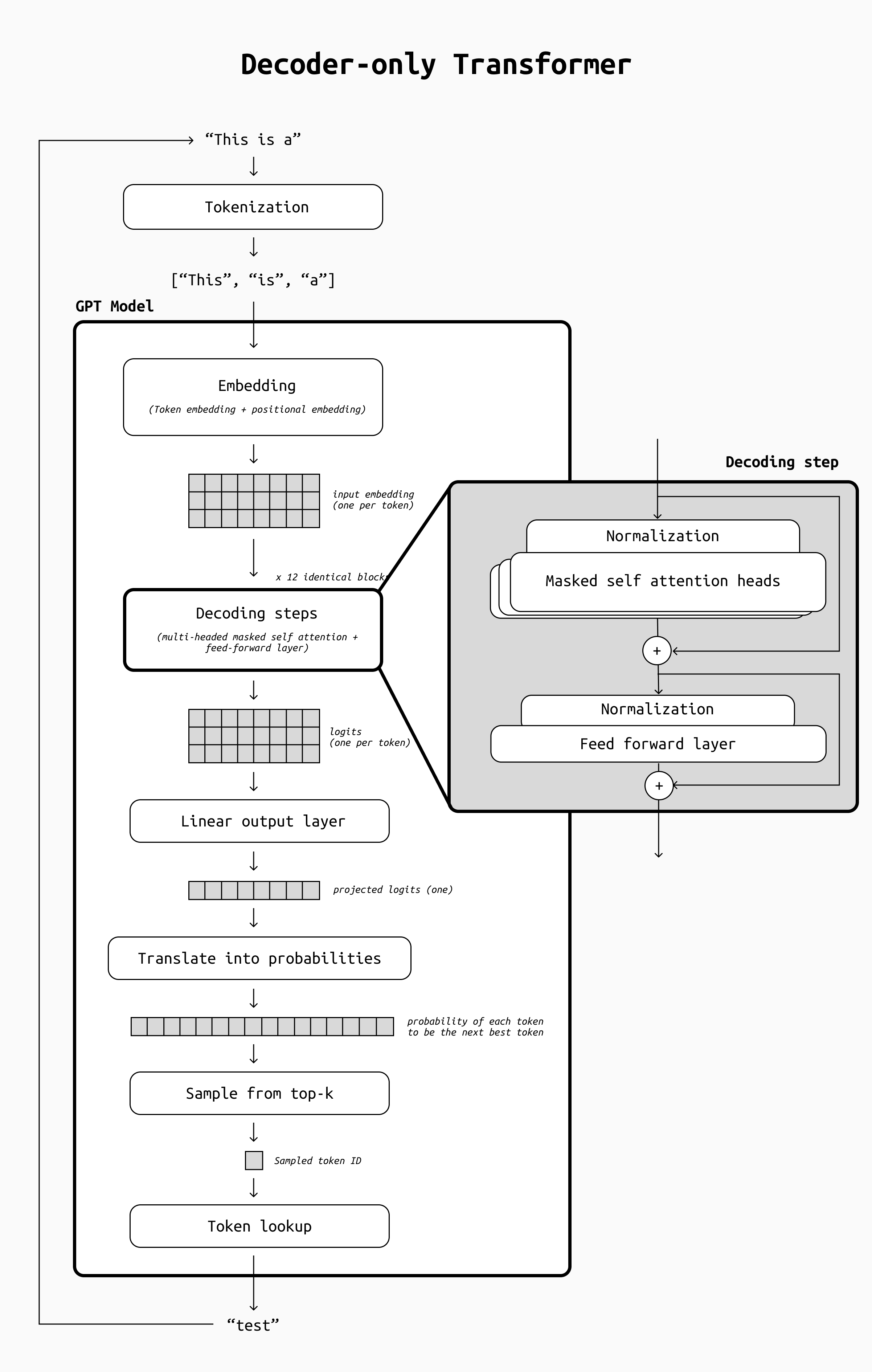

Nearly all popular LLMs share the same internal structure: they are decoder-only Transformers. However, they are not completely identical: in order to speed up training, increase intelligence or improve inference speed and cost, this base template is sometimes modified a bit.

One popular variant is the so-called MoE (Mixture of Experts) architecture: a neural network design that divides the model into multiple independent sub-networks called "experts". For each input, a routing algorithm (also called gating network) determines which experts to activate, so only a subset of the model's parameters is used during each inference pass. This leads to efficient scaling: models can grow significantly in parameter size without a proportional increase in computational resources per token or query. In short, it enables large models to perform as quickly as smaller ones without sacrificing accuracy.

But what are these expert networks, and how are they built? One common misconception is that the "experts" of MoE are specialized in a well defined, recognizable type of task: that the model includes a "math expert", a "poetry expert", and so on. The query would then be routed to the appropriate expert after the type of request is classified.

However, this is not the case. Let's figure out how it works under the hood.

The MoE architecture

In order to understand MoE, you should first be familiar with the basic architecture of decoder-only Transformers. If the diagram below is not familiar to you, have a look at this detailed description before diving in.

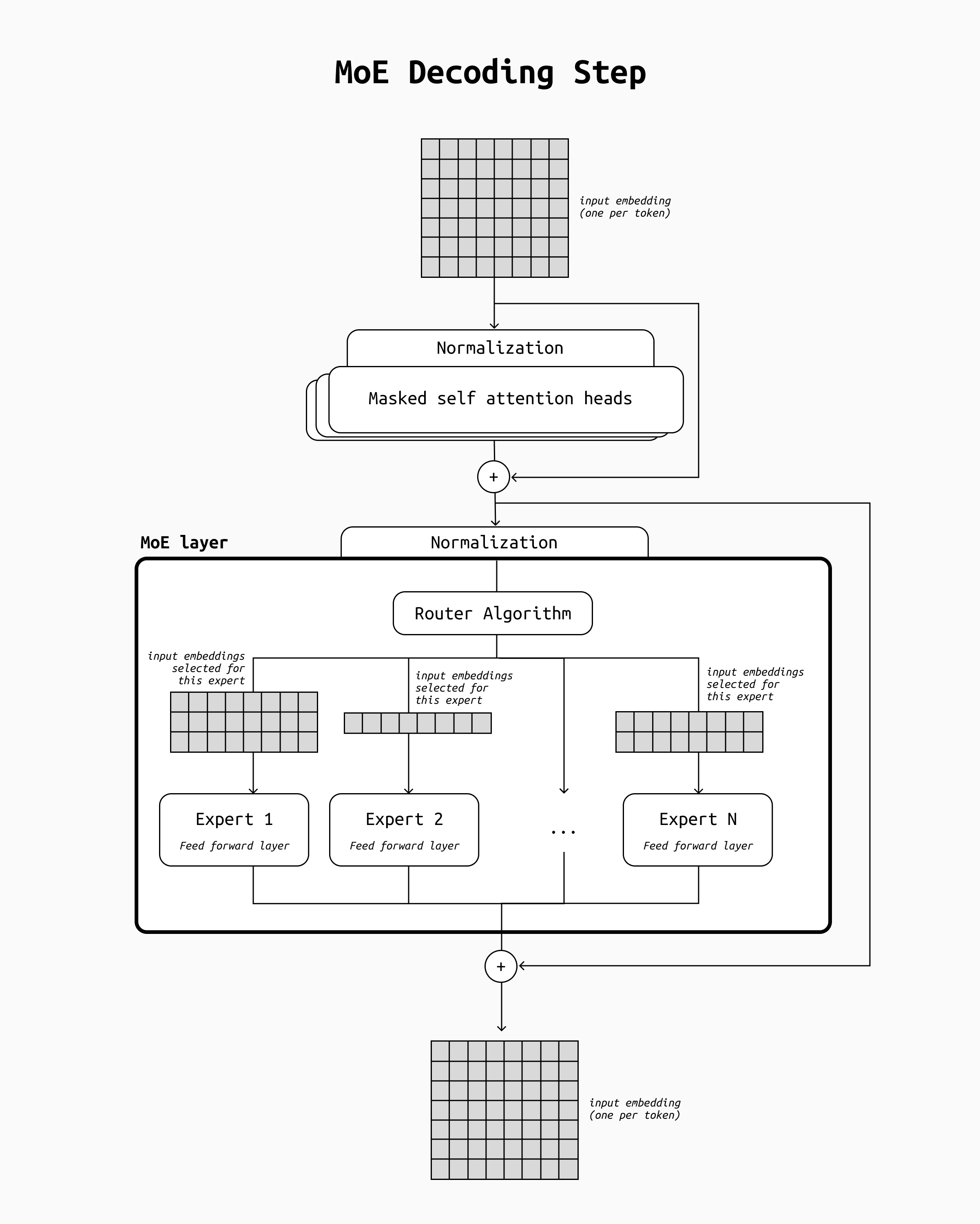

The main change made by a MoE over the decoder-only transformer architecture is within the feed-forward component of the transformer block. In the standard, non MoE architecture, the tokens pass one by one through a have a single feed-forward neural network. In a MoE instead, at this stage there are many feed-forward networks, each with their own weights: they are the "experts".

This means that to create an MoE LLM we first need to convert the transformer’s feed-forward layers to these expert layers. Their internal structure is the same as the original, single network, but copied a few times, with the addition of a routing algorithm to select the expert to use for each input token to process.

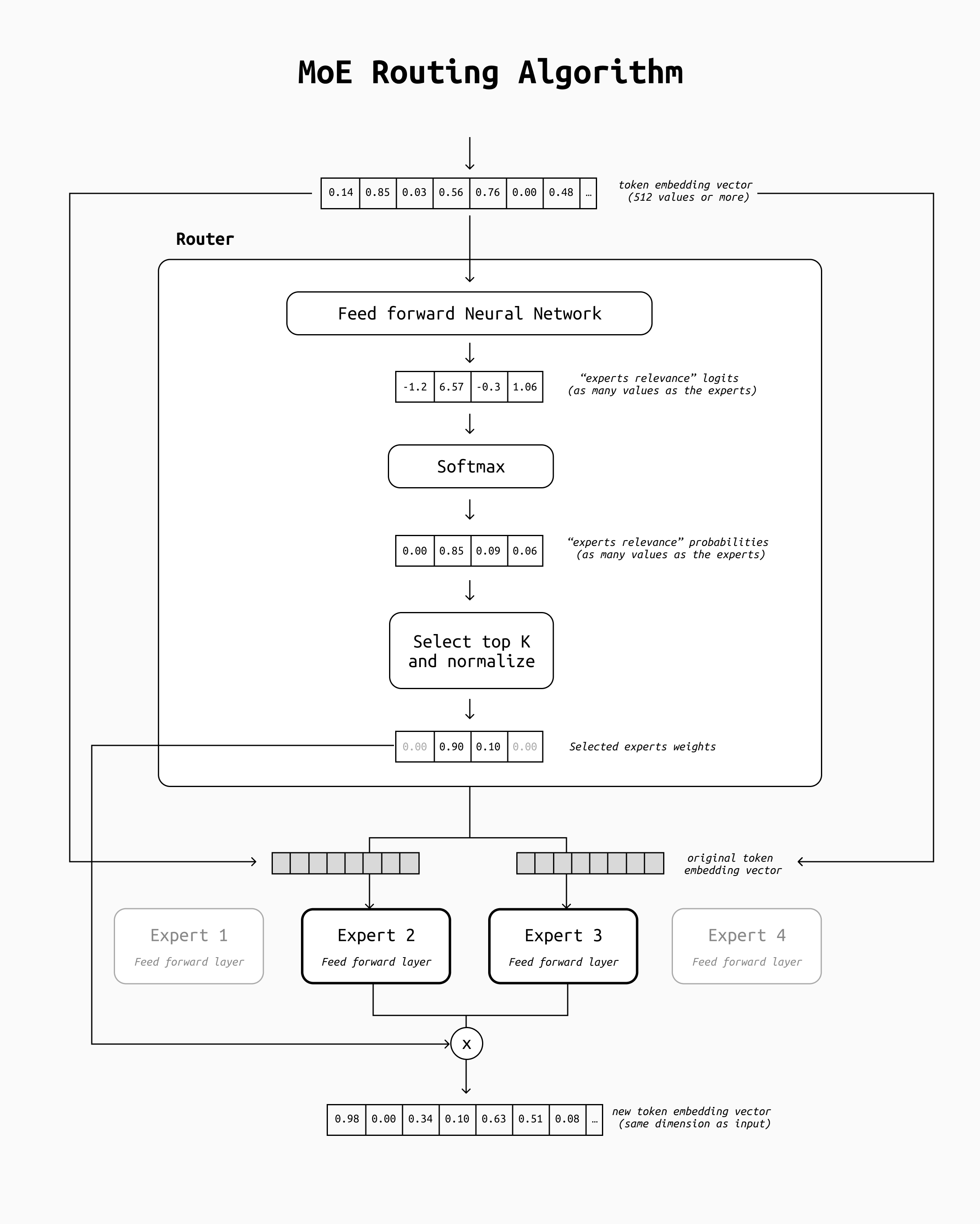

The core of a routing algorithm is rather simple as well. First the token's embedding passes through a linear transformation (such as a fully connected layer) that outputs a vector as long as the number of experts we have in our system. Then, a softmax is applied and the top-k experts are selected. After the experts produce output, their results are then averaged (using their initial score as weight) and sent to the next decode layer.

Keep in mind that this is a simplification of the actual routing mechanism of real MoE models. If implemented as described here, through the training phase you would observe a routing collapse: the routing network would learn to send all tokens to the same expert all the time, reducing your MoE model back to the equivalent of a regular decoder-only Transformer. To make the network learn to distribute the tokens in a more balanced fashion, you would need to add auxiliary loss functions that make the routing network learn to load balance the experts properly. For more details on this process (and much more on MoE in general) see this detailed overview.

So experts never specialize?

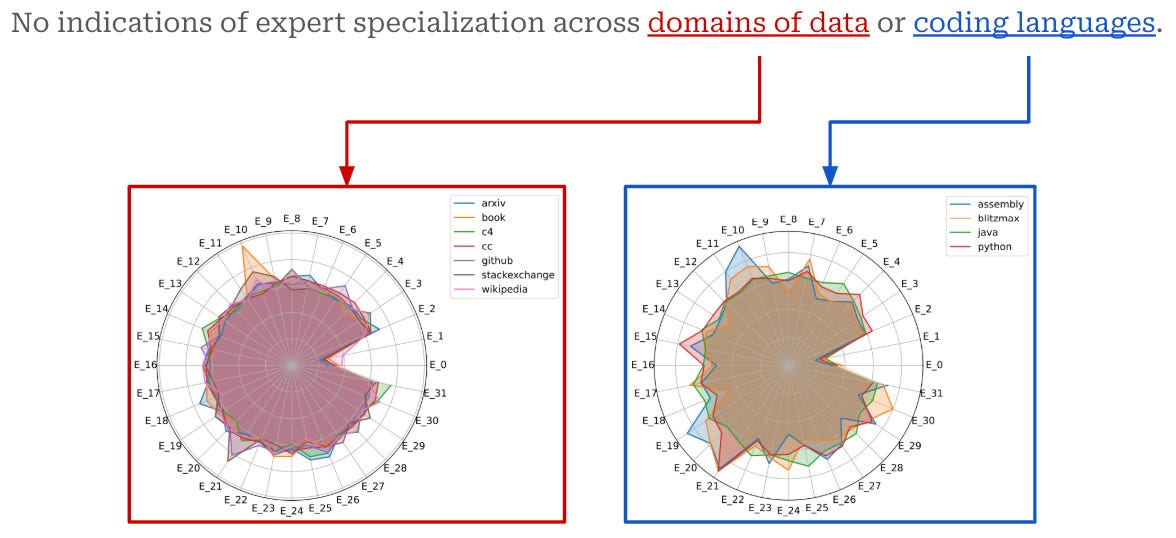

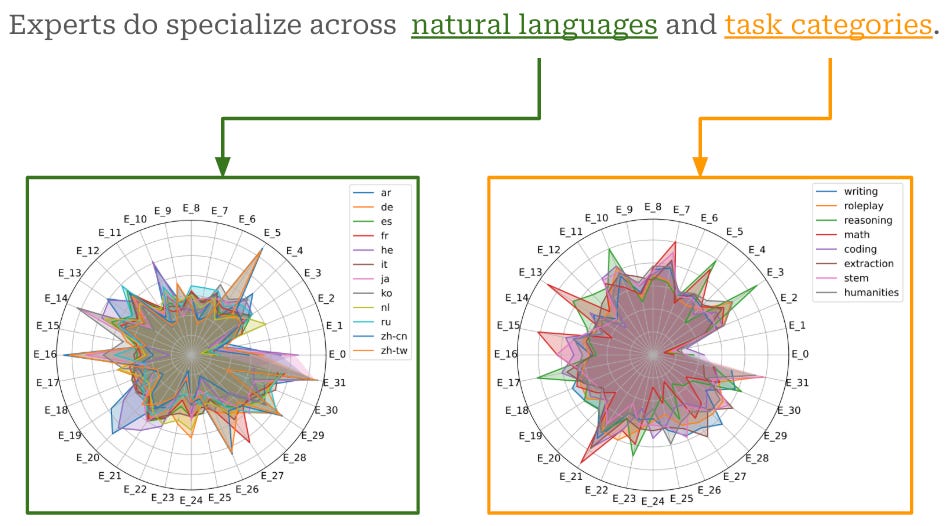

Yes and no. On the OpenMoE paper, the authors investigated in detail whether experts do specialize in any recognizable domain, and they observed interesting results. In their case, experts do not tend to specialize in any particular domain; however, there is some level of expert specialization across natural languages and specific tasks.

According to the authors, this specialization is due to the same tokens being sent to the same expert every time, regardless of the context in which it is used. Given that different languages use a very different set of tokens, it's natural to see this sort of specialization emerging, and the same can be said of specific tasks, where the jargon and the word frequency changes strongly. The paper defines this behavior as “Context-Independent Specialization”.

It's important to stress again that whether this specialization occurs, and on which dimensions, is irrelevant to the effectiveness of this architecture. The core advantage of MoE is not the presence of recognizable experts, but on the sparsity it introduces: with MoE you can scale up the parameters count without slowing down the inference speed of the resulting model, because not all weights will be used for all tokens.

Conclusion

The term "Mixture of Experts" can easily bring the wrong image into the mind of people unaccustomed with how neural networks, and Transformers in general, work internally. When discussing this type of models, I often find important to stress the difference between how the term "expert" is intended by a non technical audience and what it means in this context.

If you want to learn more about MoEs and how they're implemented in practice, I recommend this this very detailed article by Cameron Wolfe, where he dissects the architecture in far more detail and adds plenty of examples and references to dig further.